I’m examining the impact Star Trek: The Next Generation had on my formation. The introduction to this series can be seen here.

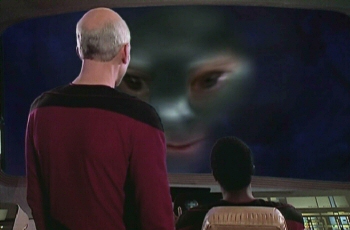

The Enterprise is pulled into a localized phenomenon they’re studying, becoming a rat in a larger being’s experiment.

This is a basic escape-from-a-snare plot, done fairly well. There’s some awkwardness of role and relationship on the ship. But it’s an eerie and soon frightening trap with well-accomplished spatial confusion and wonderful use of sound and silence to heighten the tension. It also has a welcome focus on their role as explorers, as learners and investigators instead of fighters.

What was important to me then were various points of both character development and, sometimes, remarkable wisdom:

+ When Data is pressed to parse out some understanding of the mysterious phenomenon from a lack of data, he says, “The most elementary and valuable statement in science, the beginning of wisdom, is ‘I do not know.’ I do not know what that is.†Embracing the unknown is fundamental to just about every element of life for me, and I expect this moment helped guide me in that direction.

+ Picard feels that his ship runs best when officers share freely what’s on their mind; he says this, and acts on it. Though the final decision is his, he supports his officers in collaborating with one another and in contributing richly to the discussion that Picard uses to reach his decisions. Collaboration is kind of a basic default setting for me, by temperament. But as far as having role models to learn the actual skills, Picard was my first.

+ When measurements that Data’s taken don’t yield the results she’s expecting, Dr. Pulaski turns to the others to say, “It does know how to do these things, doesn’t it?” She gets quite a few looks, and is assured of Data’s competency by the captain.1 It occurs to her that she might be out of line somehow, so she then says to Data, “Forgive me, I’m not used to working with nonliving devices… forgive me again, your service record says that you are alive. I must accept that.” Despite the fact that Data is a Starfleet officer, she still finds it incomprehensible to treat him as a living being. Her inability to perceive him as sentient grows more and more ludicrous, and annoys me as much now as it did then. Again, either the writers intend for her to be a truly obnoxious character, or they believe her responses to Data are understandable on some level. Perhaps they’re trying to illuminate what prejudices Data must deal with, or setting the stage to question his personhood further and more directly. But it’s at the expense of any likeability or sense on Pulaski’s part. My response as a 14-year old was based on my desire to defend Data in particular, who had become my friend. But as an adult, I find myself angry that anyone is being treated this way. I find Pulaski’s logic and ethics to both be profoundly lacking, and consider her to be as dangerous as anyone else who so easily negates the personhood of someone standing right in front of them.

+ When the Enterprise appears to destroy an entire Romulan ship threatening them, there are expressions of delight, relief, and accomplishment among the crew. This disappoints me. This show rarely reinforces the idea that our enemies are wholly evil and worthy of death. This is an odd moment to see.

+ The entity that has trapped them eventually decides to explore how they die, and explains to Picard that it will kill a third to a half of the crew to accomplish this. Picard refuses to allow this to happen, and authorizes an auto-destruct for the whole ship. He could have allowed them to be toyed with; he could have submitted to the entity and tried to keep some of them alive at the expense of others. But he chose dignity and integrity over simple survival. It was the only example I’d seen, outside war, of certain values being more important than one’s life. This kind of example would certainly shape my spiritual life as I grew into ideals of nonviolent resistance.

+ The entity that has trapped them eventually decides to explore how they die, and explains to Picard that it will kill a third to a half of the crew to accomplish this. Picard refuses to allow this to happen, and authorizes an auto-destruct for the whole ship. He could have allowed them to be toyed with; he could have submitted to the entity and tried to keep some of them alive at the expense of others. But he chose dignity and integrity over simple survival. It was the only example I’d seen, outside war, of certain values being more important than one’s life. This kind of example would certainly shape my spiritual life as I grew into ideals of nonviolent resistance.

+ After Picard has ordered the autodestruct, there is a 20 minute delay for the crew to prepare. Picard finds himself being asked whether he believes in an unchanging afterlife of some sort of paradise, or if death is just a door into nothingness?3 He replies:

Considering the marvelous complexity of universe – its clockwork perfection, its balances of this against that, matter, energy, gravitation, time, dimension – I believe that our existence must be more than either of these philosophies, that what we are goes beyond Euclidian or any other practical measuring systems and that our existence is part of a reality beyond what we understand now as reality.4

This was mind-blowing at 14, when I hadn’t given much thought to any afterlife, and when I desperately wanted to leave the distorted reality I was in. What was more transformative than anything else about it, though, was the repeating pattern of finding a third option when offered only two. I am realizing I learned a lot about the act of queering from Captain Picard.

1. At the time, the rest of the crew’s response to Pulaski felt like them tolerating a bully, and my current opinion’s not too far away from that. I appreciate the maturity of friends not leaping to Data’s rescue, but I also wish someone would call out her shitty behavior.

2. From http://thecia.com.au/star-trek/next-generation/201b/

3. I’m wary of how religion will be treated as a whole in the series. What I remember of it being directly addressed seemed to revolve around magical thinking and, at best, a mythic-literal faith. I hope the narrow description of the afterlife here is not intended as a stand-in for most religious concepts of death.

4. Yes, it’s a long sentence. And yes, Patrick Stewart knocks it out of the goddamn park. (Actually, just go ahead and assume that last sentence goes without saying as a footnote to every episode.) Apparently he also quoted from this speech at Gene Roddenberry’s funeral.